In 2016, the EU brought into effect the Fourth Railway Package, a programme of changes to rail regulations across the EU.

The package, which includes reforms in standards and authorisation for rolling stock, workforce skills, and independent management of infrastructure, was devised in an attempt to lower EU rail subsidies. The main strategy behind the package is to liberalise domestic rail passenger services across Europe – combatting railway companies’ ability to raise prices if they dominate both tracks and trains.

The package is split into two fields, the technical pillar and the market pillar. The technical pillar moved the authorisation process for rail from national authorities to one central European authority, the European Union Agency for Railways, reducing costs and leading to faster approvals, while also harmonising technical regulations to guarantee the same level of national market access across EU states.

The market pillar in the Fourth Package, the culmination of gradual market opening that started with the first railway package introduced in 2001, opened up long-distance European rail markets, brought public tendering in as a standard process, and legislated non-discrimination of train path allocation and infrastructure charging.

In effect, this opened routes in the European railway market to any European rail operator, public or private, regardless of the country in which the route is operated or the country the operator is based in – and in turn, ramped up competitivity, driving down prices for travellers.

EU rail hegemony facing new competition

The liberalisation of rail in Europe meant that incumbent operators have found themselves facing new competition – or in some cases creating their own competitors.

German national operator Deutsche Bahn (DB) is now coming up against FlixTrain, an open-access operator run by budget long-distance coach operator FlixBus. Aimed at the low-cost market, FlixTrain’s operations are designed to work in harmony with FlixBus’s routes, simplifying connections between budget road and rail travel. As of the end of 2022 FlixTrain, which opts to lease instead of owning its own rolling stock, has a domestic network that covers 70 destinations, as well as services in both Sweden and Switzerland.

Whereas FlixTrain is working to capture the low-cost market, where travellers are willing to put up with longer journeys due to lower prices, open access operator Nuovo Trasporto Viaggiatori (NTV) is taking on Italian operator Trenitalia on high-speed routes through its Italo brand. Italo operates a fleet of Alstom rolling stock on Italy’s high-speed network, mainly Alstom AGV trainsets but also utilises some Alstom Pendolino models as well.

Italo has been broadly successful since launching back in 2012. NTV, the first open access operator in Europe, reached its fiscal break-even point for the first time in 2016, becoming profitable since then. In 2018, NTV was sold for €1.98bn to the international fund manager Global Infrastructure Partners III (GIP); and in September 2018, German insurance giant Allianz acquired an 11.5% stake in NTV from GIP.

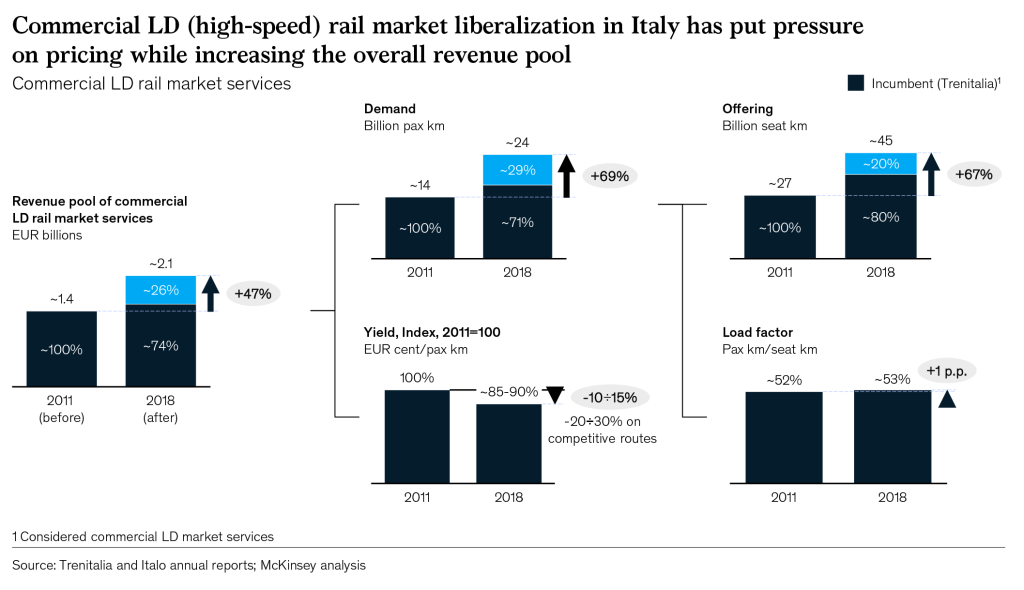

Despite Italo shifting Trenitalia’s 100% market cap – the open access operator acquired a 29% market cap by 2018 according to management consulting firm McKinsey & Company – Trenitalia actually saw an increase in revenue during that period. High-speed rail was, and is, competing with low-cost flights, and despite the shift in market cap between the two train operators, they were actually winning more passengers from air to rail overall than from one another. In fact, the rise of high-speed rail in Italy was directly named as one of the contributing factors to the demise of Italian flag carrier Alitalia in 2021.

The growth of both Italo and Trenitalia is also thanks to the fact that Italo’s growth was due to induced demand: if you build it, they will come. Or, you could say that the market for low-cost high-speed rail didn’t exist until Italo created it. The fact that an established high-speed operator can operate alongside a budget option, while both flourish, may well have been behind France’s national operator SNCF launching its own low-cost competitor, Ouigo.

Ouigo operates both conventional and high-speed routes and uses a lot of the practices that have made low-cost airlines so effective. Tickets are only available for purchase online, reducing operational costs, with the base offering featuring minimal amenities and additional features such as charging per luggage item, for pets to travel, or seats next to power sockets.

Ouigo is, overall, a worse experience than traditional rail services. Additional charges make for more complicated ticketing (and perhaps some surprise fees on the day of travel if you want to travel with, say, luggage), lower levels of comfort levels (reduced legroom) and a restricted timetable have led to criticisms – with Mark Smith (The Man in Seat Sixty-One) calling it “a train for flyers, not those who enjoy the relaxed nature of ‘regular’ rail travel”.

But as with operators in Italy, you can see the induced demand that Ouigo has created in its success. People will put up with cheap service for cheap prices, and travellers on a budget will pick the train over the plane when the existing rail passengers may not.

High-speed rail showdown in Spain

While Ouigo was having what you might call a friendly fight with its parent company SNCF in France, arguably the real success was showing a proof-of-concept for future operations further afield.

Spanish railways opened to open access operators in 2020, thanks to the Fourth Rail Package, and SNCF wasted little time moving into a new market, thanks to the central approval process through the European Union Agency for Railways. In 2021, Ouigo Espana was launched with an inaugural route on the high-speed line between the capital Madrid and Spain’s second most populous city, Barcelona, connecting Tarragona and Zaragoza along the way.

Competing with Spanish operator Renfe’s high-speed AVE brand, Ouigo Espana has been a success so far, transporting over two million passengers on the Madrid-Barcelona route in its first year. Although journey times are essentially the same across operators, Ouigo Espana tapped into the budget market; as Ouigo had in France.

Renfe followed suit, launching its own low-cost service, Renfe avlo, in 2021. Despite two other high-speed services on the route existing; avlo succeeded, boasting over 90% occupancy rates on the route. The operator has since launched a Madrid-Valencia route, with services from the capital to Seville also planned for the future.

As if three operators weren’t enough, a fourth, Iryo, launched operations on the Madrid-Barcelona high-speed route in November 2022. The service seems to be pitched as a mid-point between Renfe’s AVE and the budget options of Ouigo and avlo. Jointly owned by Trenitalia, Spanish airline Air Nostrum, and the infrastructure investment fund Globalvia, Iryo sits between Ouigo/avlo and AVE for cost and offers more luxurious facilities than the budget operators, such as 5G connectivity, on its Frecciarossa 1000 rolling stock.

Where Ouigo and Italo created their own demand, Iryo is perhaps hoping it can carve out a third middle ‘premium-budget’ market out of the existing options for passengers. Either way, with four operators vying for custom, the Madrid-Barcelona high-speed line is now the most competitive route in Europe; leaving passengers with a choice between different levels of quality, price, and availability. Time will ultimately tell whether having four competing operators on one route is sustainable, but for now the prospects certainly look positive.

The liberalisation of European rail is opening up other new possibilities for operators across the continent, and increased competition ultimately leads to a better service for the customer. Renfe is reportedly even looking into breaking Eurostar’s monopoly on the Channel Tunnel route between London and Paris. In the UK, open access operator Lumo has been somewhat successful in onboarding those who would either fly between London and Edinburgh or use LNER’s more costly service.

Passengers want more sustainable travel options compared to the carbon footprint of aviation; and if restrictions on domestic air routes continue, we may see a great modal shift to rail in the future across the continent. If in doubt, look where the money is. The fact that one of the world’s largest insurers and financial services groups, Allianz, holds a major stake in Italo; and that Iryo is part-owned by a Spanish airline that is directly threatened by rail travel; might show just how serious the open access rail competition is.