Evolution of Hyperloop Rail Technology

When Virgin Hyperloop chief technology officer and co-founder Josh Giegel and director of passenger experience Sara Luchian stepped onto the company’s custom-built pod for the first time, they knew they were making history.

“I was very excited, and I think if there were any nerves it was just about the magnitude of the moment and realising that we were potentially about to be writing history,” Luchian told Railway Technology.

On 8 November 2020, the company made worldwide headlines when it conducted the first passenger test on its hyperloop system. The trial, which was carried out in the Nevada desert, was considered a success by Virgin Hyperloop’s partner the Virgin Group.

Even though Virgin Hyperloop started working on the project in 2019, the development of hyperloop technology dates back years, further even than a research paper published in 2013 by Tesla CEO Elon Musk.

As hyperloop projects come to fruition around the world, we explore the evolution of the concept, from its origins to the ground-breaking futuristic networks being built today.

18th and 19th century: imagining the hyperloop’s precursors

Musk’s idea to build a super-fast alternative to trains, which would travel through a series of low-pressure tubes and be powered by a vacuum and maglev system, was based on studies dating back at least three centuries.

One of the first people to ever imagine a prototype of the hyperloop was British inventor George Medhurst in the 18th century. Medhurst, who pioneered the use of compressed air as means of propulsion, filed a patent for a system that could move goods through a system of iron pipes in 1799.

In 1845, the London and Croydon Railway built an experimental cargo station in which a vacuum was created between the rails and the train, causing it to be propelled forward by atmospheric pressure. Even though the Croydon railway experiment was abandoned two years later, by 1850 pneumatic cargo railways started to appear also in other parts of Europe, such as Dublin and Paris.

During the mid-1860s, the Crystal Palace atmospheric railway was built in south London and ran through Crystal Palace Park for several months. The system featured a fan that was 22ft in diameter to propel the train. For return journeys, the fan’s blades would reverse, sucking the carriage back along the tracks.

20th century: levitating pods and air cushion technology

In his research paper, Musk acknowledged US rocket scientist Robert Goddard as one of the first to ever design a hyperloop.

In 1909, Goddard wrote an article entitled ‘The Limit of Rapid Transit’, where he described a train that would travel from Boston to New York in only 12 minutes. Even though it was never built, the project included some of the hyperloop’s building blocks such as the presence of levitating pods and a vacuum-sealed tube.

After World War II, attempts were made to build a system similar to the hyperloop. These included the Aerotrain, which was developed in France between 1965 and 1977.

Designed by French scientist Jean Bertin, the Aerotrain’s prototype was similar to a levitation train but relied on cushions of air instead of magnetic resistance for propulsion. However, a lack of funding, the cost of infrastructure and Bertin’s death in 1975 spelled the end of the project.

In the 1990s, a team of Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers spearheaded by Professor Ernst Frankel started to develop a vacuum-tube train that would take 45 minutes to go from New York to Boston. Even though a test loop was built, the project was eventually shelved.

The 2000s: from ET3 to Elon Musk

In the early 2000s, US consortium ET3 Global Alliance CEO Daryl Oster designed a maglev train in which car-sized pods travelled in elevated tubes.

Patented in 1999 through an open consortium model, ET3 stands for Evacuated Tube Transport Technologies, which refers to a “network of tubes that have air removed to eliminate friction for magnetically levitated and driverless capsules”.

While Musk first mentioned the hyperloop in 2012 at an event organised by technology publication PandoDaily, it was only in August 2013 that he revealed the first design.

In a 57-page document, Musk detailed how Hyperloop Alpha would be made up of enclosed capsules or pods – each containing up to 28 people – moving through a system of tubes on skis that levitated on a cushion of air.

Proposed as a faster and electric-powered alternative to the California high speed rail, Alpha Hyperloop would connect San Francisco to Los Angeles in 35 minutes and cost $6bn.

Just as Oster did in 1999, Musk decided not to patent it for himself, but instead registered the design using the open source project model.

2013-2020: make way for hyperloop

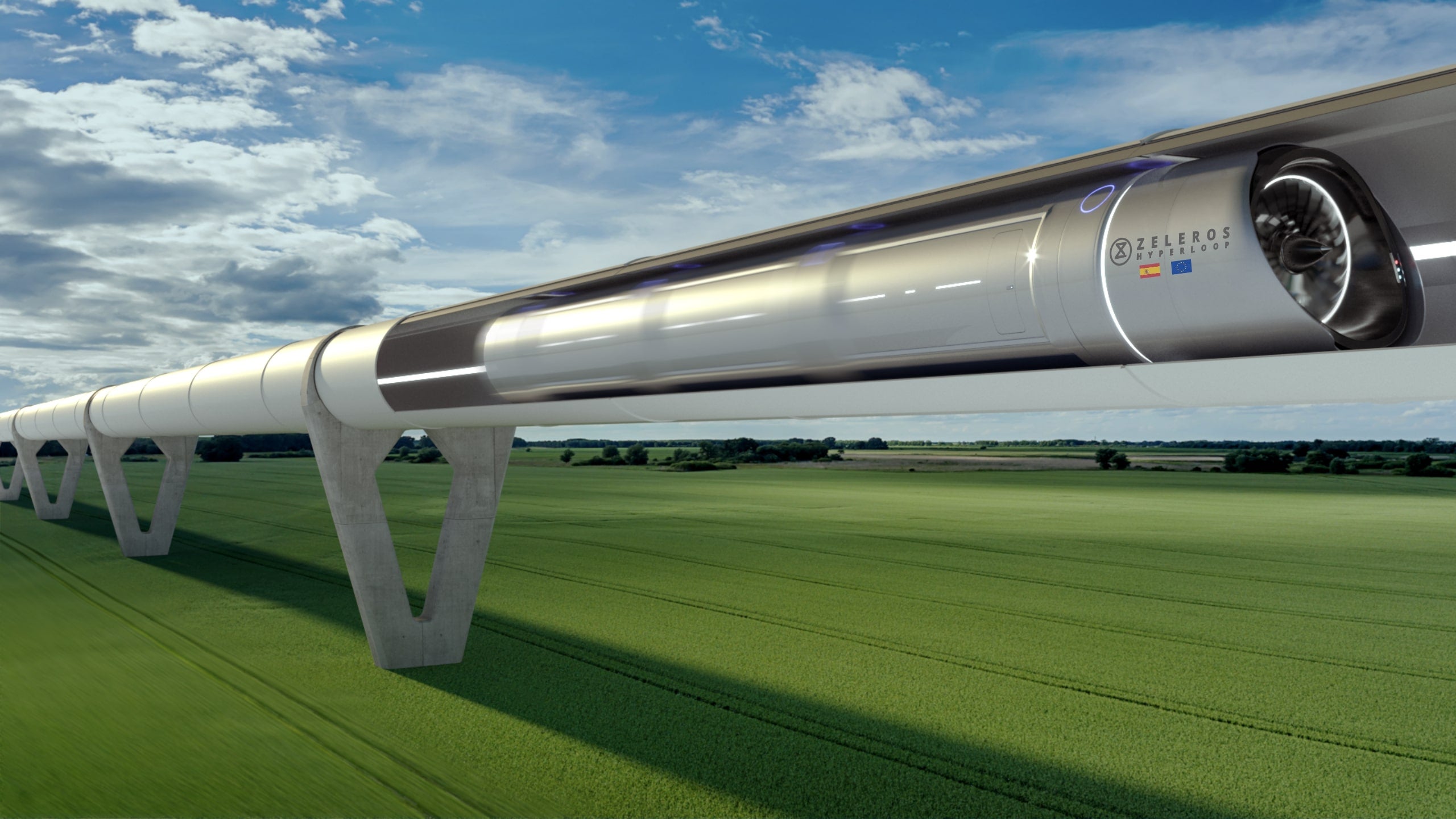

In the years between 2013 and 2020, a handful of companies – including Virgin Hyperloop and Zeleros – started working on developing the hyperloop from Musk’s designs.

Formerly known as Hyperloop Technologies and Hyperloop One, Virgin Hyperloop started to actively work on the hyperloop in May 2016, when it successfully carried out its first open-air test in North Las Vegas. “Our growing team of incredible engineers is working at full-speed along a proven development process to design, analyse, build and test the hardware and software to make Hyperloop a reality,” commented co-founder NV. Brogan BamBrogan.

Two months later, the company presented its first feasibility study, showing the economic and environmental positive impact of a potential 500km hyperloop connection between Helsinki and Stockholm, reducing travelling times between the two Scandinavian capitals to 28 minutes.

In March 2017, the company showed the first images for its hyperloop development site, which was built in the Nevada desert. With a diameter of 3.3m and a length of 500m, DevLoop was the world’s only full-system and full-scale test-site.

“Our team of more than 150 engineers, technicians and fabricators have been transforming what was, just over five months ago, a barren stretch of desert, into a hive of activity and now home to the world’s first full-scale Hyperloop test site,” commented Giegel at the time.

In July 2017, the company announced that it had successfully completed its first full system hyperloop test in a vacuum environment. The vehicle cruised through the first part of DevLoop for 5.3 seconds, achieving 2Gs of acceleration and achieving a speed of 69mph.

In August of the same year, it was revealed that Hyperloop One had travelled at a speed of 2.7 times the one achieved in the first trial, reaching 192mph compared to 69. The prototype had also travelled longer, covering the whole 500m DevLoop distance.

After showcasing the project’s design around the world and carrying out passenger application demonstrations, in October 2020 Virgin Hyperloop successfully carried out its first passenger test.

2020: Zeleros secures new funding

Founded after winning the Best Hyperloop Proposal Prize and Best Hyperloop Propulsion Prize at the SpaceX-sponsored 2015 Hyperloop Pod Competition, Valencia-based Zeleros Hyperloop began working to make its prototype a reality in 2016.

After raising technological and economic support, the company joined forces with Siemens in June 2019 to develop the technology and infrastructure necessary for the project.

“Our approach brings two main benefits,” CEO David Pistoni told Railway Technology. “The first one is to reduce infrastructure costs and maintenance, while the second is to have some kind of aerodynamic propulsion inside the vehicle, in a way similar to an aeroplane while being 100% electric.”

In June 2020, the company managed to secure €7m, completing the financing stage. “The next steps will require building a complete vehicle, to integrate all the technologies we have already validated at the laboratory scale, and our test track to run it in operational conditions,” added Pistoni.