Designing a station is like tackling a jigsaw puzzle with over a thousand pieces. There’s a myriad of things to consider, and they all need to fit together in order to complete the puzzle.

Many people think the role of a train station designer or architect revolves around creating statement features like glass roofs, but the reality is very different. Their challenge is to arrange spaces as efficiently as possible, driving value and reducing costs, all while creating a building that fulfils a long list of requirements from clear wayfinding to urban connectivity.

They’re also seeing their roles evolving. Where once they would be provided with a detailed brief, now they’re given a blank canvas.

“I’m not someone who’s used to figuring out what a space is going to be used for,” laughs Marla Gayle, managing principal and transportation practice lead at US architectural, urban planning, and engineering firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM).

“Usually someone gives me a program and I design something to meet that. But in many instances now, it’s a case of ‘we have a big space here, what can we do with it?’.”

Humanising the experience

There are, however, a range of themes that are gaining importance, such as the passenger experience.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataIn the past, the focus was on functional requirements and technical performance; today it’s increasingly about providing a more experiential level of passenger service, as Julian Robinson, a consultant at Engineering consultancy Robinsons Associates and ex-head of architecture at Crossrail, explains.

“It’s all about people. With Crossrail we wanted to provide a space that was more relaxed, cleaner, simpler, and would cater for a wider range of users than just commuters. More attention was spent on making sure it became more of a human experience to move through the station.

“The curved corners, for example, came from trying to get the efficiency of flow, but also helping people to relax and feel secure because they can always see where they’re going and not bump into people,” he explains. “There’s warmer, calmer lighting on the platforms, everything’s clean and uncluttered and there’s a simplicity of signing so people can easily see where they need to go.”

This theme is the same globally, as Jorge Borrelli, principal of US architecture and planning company Borrelli + Partners, highlights.

“Big Time Design Studios and Borrelli were asked to design Brightline’s station at Orlando International Airport to have lots of natural light and be more aligned with a hotel lobby than a traditional station,” he notes.

Urban gateways: more than just stations

There’s also more of a focus on urban connectivity, with designers working on creating stations that are intermodal hubs for a city’s different transport options.

“We’re working on some really interesting projects in Tel Aviv, developing concept designs for intermodal hubs that connect all the new infrastructure initiatives happening there,” says Peter Fajak, associate director at SOM.

“Similarly in Atlanta, the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) Five Points station transformation project is all about improving connectivity between all the rail lines and the city’s bus system,” adds Gayle.

There is also a move away from thinking about stations in isolation, instead making them a key part of the community they serve. People are thinking of them more as public spaces they can use for a variety of means, from somewhere they can move through on their morning jog, to a place to meet friends for lunch or a drink.

“We’re providing routes through the city, rather than blocking the way that people want to move,” says Declan McCafferty, a partner at architect firm Grimshaw.

“We’re creating stations with entrances in multiple directions, encouraging walkability and active travel, linking them up to the surrounding streets to support local economies, but also delivering a place people will want to spend time in.”

A civic purpose

“These spaces have a civic purpose,” continues Gayle. “MARTA has a programme called Station Soccer, where they make room for a soccer field at each of their stations for local kids’ groups to use during the day and at weekends. They also have a community garden alongside a station.”

With this in mind, as well as linking back to the humanising of station spaces, we’re seeing more use of art in station design.

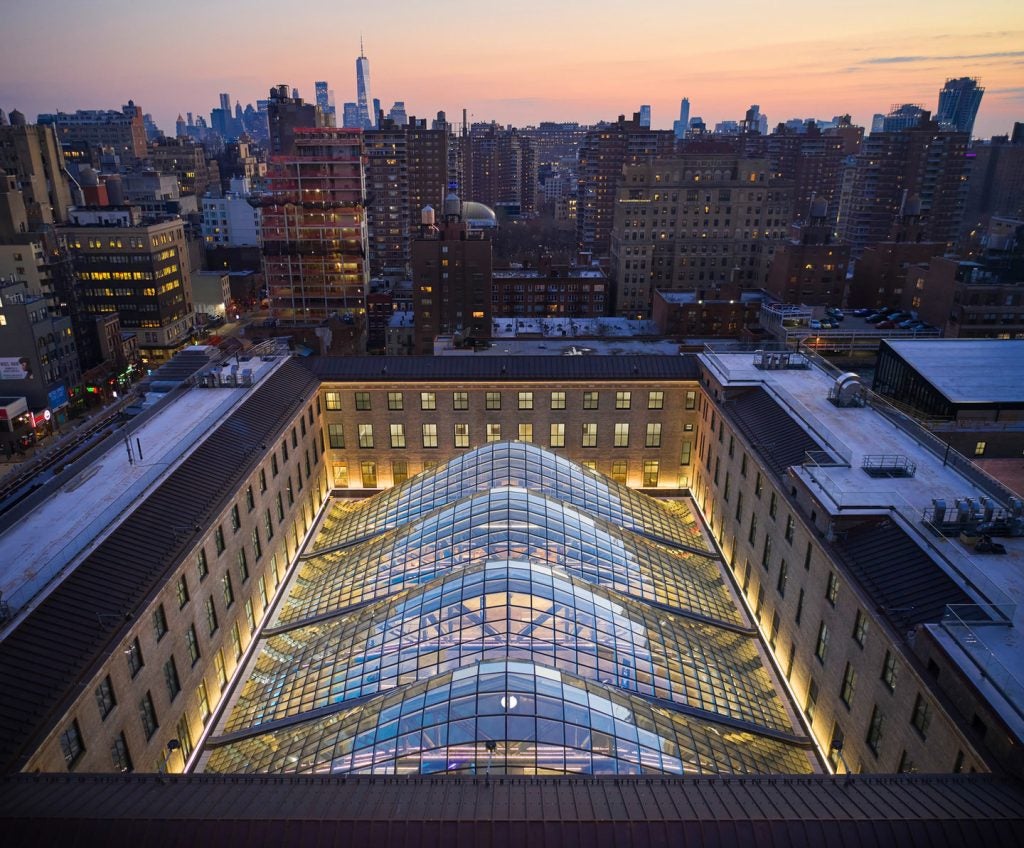

Crossrail had an art programme, for example, creating pieces of interest across Elizabeth Line stations, while SOM architects integrated art into the design of Moynihan Train Hall, as part of the Penn Station expansion. Look up inside the 31st and 33rd Street entrances and you’re greeted by artwork on the ceiling.

“This opened during the pandemic, and it became a place that people came to just to see the art. It was a stunning statement about what these kinds of spaces can be, and how they can become a part of the local community,” says Gayle.

Another example comes from the Fulton Street Transit Centre in New York. In one of the city’s deeper subway stations, artist James Carpenter created an oculus called Sky Reflector-Net, which reflects sunlight down into the stories below.

Accessibility and Sustainability

Of course, accessibility is a fundamental aspect of the design of a station. This covers everything from ensuring there are toilets and changing facilities throughout the station to providing the necessary assistance for those with limited mobility, sight, or hearing.

More thought, however, is going into providing spaces that are comfortable for the neurodiverse.

“For some people, these grand echoey spaces are the worst in the world, so how do you create different types of spaces so people can still experience the station but shelter themselves from the chaos if needed? Those are the kinds of things architects can bring to design solutions,” says McCafferty.

Sustainability is another core aspect of station design and one that’s a bigger priority than ever before.

Architecture firm 7N, for example, put sustainability at the heart of its modular design guide for small and medium stations on behalf of Network Rail. Essentially a catalogue of standard components that can be pieced together to respond to the needs of each station, it’s made up of five elements, each embedded with sustainable design principles including minimising embodied carbon and making stations as self-sufficient as possible.

“Take the ‘welcome mat’ for example; the approach to the station includes soft landscaping that provides biodiversity benefits and sustainable urban draining,” notes Ben Projects Leader, 7N Architects.

Climate resilience is another theme factored into the design of everything from entrance shading and natural ventilation through to mitigating against rising temperatures and the risk of flooding.

“Crossrail was designed with lots of anti-flood measures, such as flood barriers that automatically raise when a threshold is hit. This is something that going to become more prevalent, but rising temperatures are the bigger problem,” says Robinson.

“Underground systems ventilate by dragging air in from the outside, but if it’s 400C outside, then it’s just going to get hotter and hotter inside.”

The role and function of stations continues to evolve, which is creating new challenges for their designers as infrastructure capable of adapting to tomorrow’s needs requires the adoption of a new range of priorities. The good news is that the building blocks for next generation stations are starting to fall into place.

This article was originally published in our digital magazine Future Rail. You can subscribe to the magazine for free by clicking here.