During a 2013 meeting between Bolivia’s President Evo Morales and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping, the concept of a transnational megaproject was born, one that would join the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans by means of a modern railway, spelling the end for the current monopoly maritime shipments have on trade.

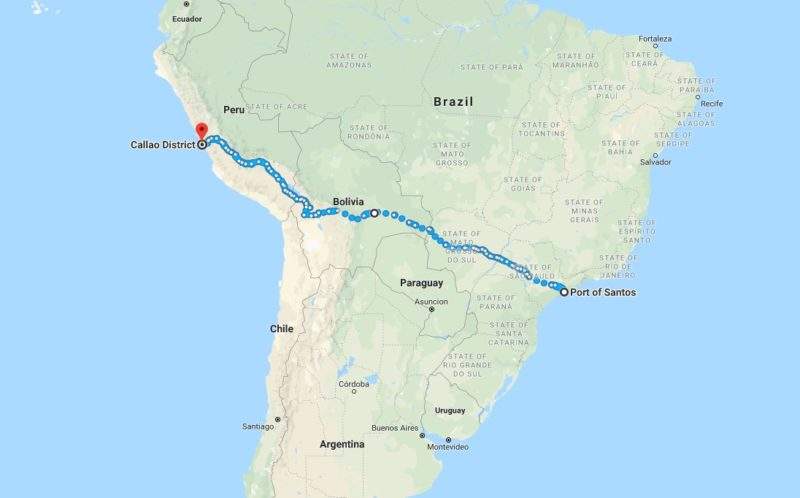

Known as the Central Bi-Oceanic Railway, the planned 3,000km route would run from the port of Puerto Santos in Brazil to Puerto de Ilo in Peru, crossing 1,700km of Bolivian territory in between.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Due to its reach and projected trade benefits, the megaproject has been dubbed ‘the Panama Canal of the 21st century’, as well as drawing comparisons with Qhapaq Ñan, a historic 35,000km network that reached Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Ecuador and gained UNESCO World Heritage status in 2014.

Since its conception, several feasibility studies have already been completed and all three South American countries involved have greenlit the project, and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) gave it its full backing.

While it’s still too soon for a fixed completion date, UNASUR secretary general Ernesto Samper Pizano hinted that in 2021, the railway would transport approximately seven million people and nearly 10,000 tons of cargo, “with great possibilities of rapid increase”. Meanwhile, separate reports indicated the inauguration date could be 2025, when Bolivia celebrates the 200th anniversary of its independence.

During their meeting at this year’s Summit of the Americas in Lima, Morales and Peru’s President Martin Vizcarra discussed accelerating construction of the Bi-Oceanic train. “A commission will work so that there is a meeting of transport ministers or public works ministers to define the finances and pre-investments of the project,” Morales said.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataTheir eagerness comes as no surprise: once completed, the corridor will substantially alter the region’s geo-political and trade relations, and will do away with the maritime monopoly currently in place.

Changing the face of Latin American trade

Throughout its coast-to-coast journey, the train will traverse rough terrain, including mountain slopes in the Andes, rivers and flood-prone regions, as well as the Amazon forests.

China’s interest in the project comes as little surprise. During his 2015 tour of Latin America, Xi Jinping pledged $250bn in investment in Latin America over the next ten years as part of a drive to boost influence in a region long dominated by the United States.

The project would make it far easier and cheaper to transport commodities from Latin America to China, particularly iron ore and soybeans from Brazil and minerals such as gold and copper from Peru.

At home, the railroad would be an equally big win. According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), South America’s countries should invest annually 6.2% of their gross domestic product (equivalent to $320bn) in order to satisfy their infrastructure demands before 2020.

The biggest winner would no doubt be landlocked Bolivia, which is why the country is spearheading the necessary research into the commercial prospects, environmental impact and construction. Currently, the country is involved in an ongoing fight for coastal access with Chile, since its lack of easy access has left Bolivia at the mercy of neighbouring economies. The Bi-Oceanic Corridor is therefore expected to drive economic growth, improve the capacity of trade relations in the region, and allow the exploitation and industrialisation of its natural resources.

Similarly, Peru’s former President Ollanta Humala said the project would “consolidate Peru’s political position as a natural gateway to the South American region” for China, a major trading partner.

For Brazil, the railway is expected to cut transportation time and reduce the cost of shipping grain to China by approximately $30 per ton. In addition, the new east-west connection will provide a welcome addition to Brazil’s current rail network, which runs mostly from north to south. Transporting goods towards the west, instead of the Atlantic, will allow from the strain to be lifted from the overloaded sea ports and adjacent infrastructure.

Interest gathering from abroad

As expected, the corridor is primed to be one of the largest infrastructure projects of the century, and as such, contract offers have already started pouring in.

According to local publication Gestión, the prospect of building the corridor in the near future stirred an “enormous interest” in Spanish companies, with 40 of them taking part in an information day organised by the Foreign Trade Institute of Spain and the Commercial Office in Bolivia.

In February, Bolivian public works minister Milton Claro also mentioned the involvement of a Swiss-German consortium made up of more than 30 companies as investors.

In the meantime, while the financing still remains to be revealed pending further negotiations, the project has had a number of evaluations completed already. Engineering and consultancy firm Ineco (which also lists other big projects such as HS2 in the UK and Saudi Arabia’s Haramain High Speed train project) has compiled an environmental assessment, focusing on the ecological and social impacts the route would have in Bolivia. According to Ineco’s website, the study was carried out between 2013 and 2014 and “aims to safeguard the vast natural heritage in the region, which consists of a multitude of natural areas with high biodiversity and improve the quality of life of Bolivian people.”

Indeed, the project has generated concern among local environmentalists, with dire warnings issued that the “room for error verges on the catastrophic”. After all, the corridor bears similarity to the Interoceanic Highway, which has recently made headlines for the deforestation of 680,000 acres of Amazonian rainforest in its path.

A press release published by the Regional Group on Financing and Infrastructure (which represents four civil society organisations from Latin America and the Caribbean) warns that four of the five possible routes of the Bi-Oceanic Railway cross natural protected areas or indigenous reserves.

César Gamboa, executive director of Peru’s Environment and Natural Resources Law, criticised the lack of transparency involved in revealing what the economic and geopolitical implications the project will have.

Whether the full assessment of its commercial, ecological and social impact will be released soon remains to be seen. Meanwhile, negotiations carry on as the project is still on the drawing board, and more diplomatic visits are expected before any ground is broken. Nevertheless, the Bi-Oceanic Corridor’s length, ambition and potential to re-write the rules of international trade certainly make it one of the rail industry’s most exciting projects to watch in the years to come.