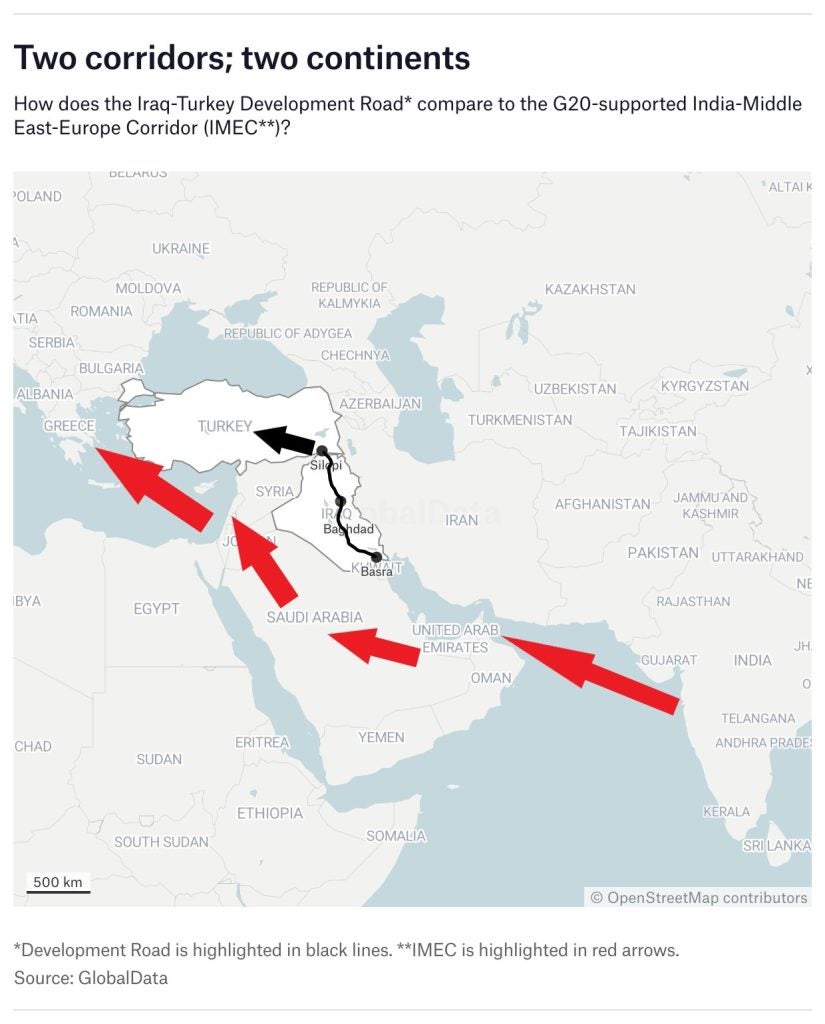

Turkish President Erdogan has announced plans for an alternative trade corridor to the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC) agreed by the US and EU at the G20 summit in New Delhi earlier this month.

According to the US and the EU, IMEC will connect Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Jordan and Israel by rail, entirely bypassing Turkey as it leads on to Europe and India by ship.

Analysts say it is a counterbalance to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Ankara, however, views IMEC as a threat to Turkey’s historically central role in transporting goods between Europe and Asia.

Erdogan said that “there can be no corridor without Turkey”, threatening to “part ways with the EU”.

A significant chunk of Erdogan’s alternative corridor relies on co-opting Iraq’s Development Road project. Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan insisted that “intensive negotiations” were underway with Iraq, the UAE and Qatar for a transport route into Turkey from the Great Faw Port in the oil-rich Basra province in southern Iraq.

Turkish-Iraqi construction begins

Construction of the $17bn Development Road is already underway in Basra.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataDesigned by Italian company Progetti Europa & Global, the project will construct railway and road lines extending from Grand Faw Port through the cities of Diwaniyah, Najaf, Karbala, Baghdad and Mosul before traversing over the Turkish border via Silopi and on to Europe. It is also predicted to provide Iraq with access to Mersin Port on Turkey’s Mediterranean coastline.

“Iraqi companies cannot manage this tremendous project alone,” Deputy Governor of Mosul Rifat Semmo told Turkish news agency Anadolu Ajansi. “Iraq needs foreign companies in this project and neighbouring Turkey is the closest country to Mosul. We need Turkish companies.”

In 2022, foreign direct investment from Turkish companies into Iraq largely revolved around Istanbul-headquartered Elkon. The manufacturing company opened three new concrete batching plants in Baghdad, Kut and Al Diwaniyah, according to GlobalData research.

As the Development Road project ramps up construction, Baghdad will expect Erdogan to build on the $5bn he pledged to Iraq’s post-ISIS reconstruction at a 2018 conference in Kuwait.

Turkish EU aspirations on ice

The Turkey-Iraq plan comes amid wider friction between Turkey and the EU.

Last week, the European Parliament released a report declaring that Turkey’s long and drawn-out EU accession cannot resume amid concerns about human rights violations and lawful processes. Amnesty International accused Turkey of baselessly convicting four human rights defenders in a months-long saga earlier this year.

Despite praise for Erdogan’s recent attempts to persuade Russian President Vladimir Putin to revive the Black Sea grain deal, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs labelled the report as “a collection of unfounded allegations”.

“The EU is trying to break away from Turkey,” Erdogan said ahead of a trip to New York for this week’s United Nations General Assembly. “We will make our evaluations against these developments and, if necessary, we can part ways with the EU.”

Turkey has made several attempts to join the EU in the last 24 years. Ankara’s accession bid was frozen in 2018 because of what the European Parliament called “democratic backsliding”.

Analysts have said this latest setback in Turkish EU aspirations is partially the result of Ankara’s continual double-agent role between Eastern and Western powers.

“Turkey has been relatively successful in juggling the big powers’ pressures on the global stage,” says Carolina Pinto, Thematic Intelligence Analyst at GlobalData. “However, current geopolitical instability may force Erdogan to pick sides. The third and most attractive option would be for Turkey to carve out its own trade corridor.”

Erdogan has long attempted to frame Turkey as the mediator between the US, EU and Russia during the Ukraine war, reaping considerable economic, diplomatic and military gains over issues such as Sweden’s NATO accession. But Turkey’s non-alignment strategy is now backfiring on multiple fronts.

On September 14, the US unleashed a wave of fresh sanctions against Russian entities, as well as landmark sanctions against five Turkish shipping companies for aiding Russian defence ministry vessels in its invasion of Ukraine.

Turkey fared little better among its supposed eastern allies at the BRICS summit on August 24.

In Johannesburg, the absence of President Putin, a long-standing friend of Erdogan, led to the group omitting Turkey from its list of six newly invited countries: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

“Exclusion from the BRICS has left Ankara bristling at its lack of involvement in current negotiations to siphon global financial power away from the US and the dollar,” according to Pinto.

Amid increasingly polarised international relations, Turkey’s ‘friend to all, enemy to none’ approach, successful for so long, looks set to lead the country into geopolitical oblivion. The outcome of this trade corridor saga may determine Erdogan’s strategy moving forward.